Can Mainstream Art Express the Rage of Normal People?

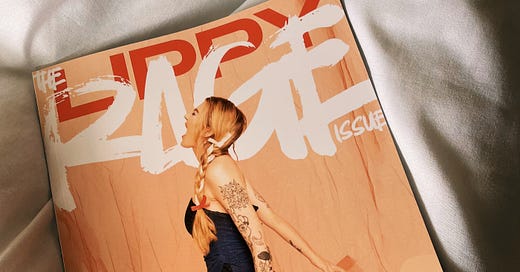

NOTE: This article was written for the latest spring/summer issue of Lippy magazine, which was centred around the theme of Rage. So much work goes into making physical print, from graphic design to editing to simply ordering the damn things. This issue is filled with insightful poetry, photography, and pieces ranging from the political to the deeply personal. I’m very grateful for my tiny contribution to be a part of this and encourage anyone reading this to keep an eye out on their website for a chance of ordering it yourself - and also just to read the wonderful articles regularly uploaded to the site.

In times of climate change, cost of living crisis, and innumerable other injustices, it's hard to ignore the rage of normal people bubbling on a global scale. The mainstream media has certainly noticed, with sociopolitical commentaries abundant in the output of popular culture. But how well can our rage be represented by these people? Or has our anger been truly commodified?

It seems almost oxymoronic for eat the rich to be so in vogue. On screen, we’ve seen additions to this genre spawning at whiplash speed with The Menu, Knives Out & Glass Onion, You, White Lotus, and Triangle of Sadness all springing to mind. Most of these take the comedic angle in their portrayals of the ruling class, crammed with characters who practically caricature the elite – think tech bros, tabloid duchesses, pretentious art critics, family fortune heirs. Of course, its been somewhat gratifying to see them ridiculed and given their come uppance. Yet, all these features leave a tad wanting in terms of actual rage and revenge. Maybe we’re at a point where we want to see a call to real revolution - with real guillotines. At the very least, it would be refreshing to see eat the rich portrayed seriously rather than wrapped up in the light-heartedness of comedy. All of these works remain somewhat safe under their humorous guises. Perhaps that's a consequence of the environment these stories are being produced in. Created by big media names like HBO and Netflix, or angled towards success at Cannes or the Oscars, these creations are trapped within a safe set of boundaries. Whilst they remain within the very systems they critique, they will never be allowed knives sharp enough to make a real stab. Or worse - they will never gain the self-awareness to recognise their own complicity.

Shallow political messaging is not resigned merely to the realms of film. Bella Mackie’s 2021 book ‘How To Kill Your Family’ falls into the eat the rich genre, humouring and mocking the idiosyncrasies of the British upper classes. Yet, it employs these stereotypes without entering into any proper critique. In fact, the embittered Grace’s revenge plot actually reinforces the elitist belief that any who hates the rich is simply jealous. Mackie’s book attempts to ridicule, but is mockery enough?

Anti upper-class sentiments are not the only types of rage being misapplied in mainstream arts. There’s been a rise in the throwaway use of weak and generalised political statements as a type of virtue signalling or anti-establishment cultural capital. Wet Leg recently rounded off their Brits award speech with a last minute ‘Fuck The Tories’. Whilst the sentiment garnered lots of praise online, it is arguably a bare minimum statement – especially when compared to others over the years who have used their award speeches to call attention to specific and urgent social issues. This is not a dig at Wet Leg specifically – they only come to mind as a recent example. It is simply calling to attention to how much more wisely, carefully, and powerfully those in the public eye could use their platform.

It seems that many mainstream attempts to express societal rage in popular arts are well-intentioned but suffer from their naïvety. ‘The News’ from Paramore’s latest album comes off rather tone-deaf in their portrayal of the endless depressing news cycle. Whilst doom-scrolling is a relatable topic, the song fails to recognise its own privilege in being able to to ‘turn on, turn off the news’. Those facing ‘war on the other side of the planet’ are not so able to escape from those harsh realities. Whilst the empathetic message of our ‘collective heart breaks’ is well-intentioned, it lacks a real depth and misses the mark. This adds a further dimension to this critique: what happens when rage is ventriloquised from a position of privilege? Does this mean Western art can never touch upon problems outside of its bubble? Or do we just need to find more authentic ways of uplifting marginalised and oppressed voices?

There are a few success stories of valuable and outsider cultural critiques breaching the mainstream. Sleaford Mods latest album has brought working class rage into the album charts as of recent with the blisteringly sardonic ‘UK Grim’. And back in 2019, Bong Joon Ho’s harrowing film on South Korean class inequality ‘Parasite’ won four Academy Awards. Yet moments of social mobility, meritocracy, or attention to non-Western voices in the arts remain few and between. The best conveyors of everyday people’s rage remains on the outside of the dominant culture, in independent and underground circles. Political rage is found in punk, in Palestinian cinema, in poetry. It’s up to us to find and uplift those voices rather than relying on the systems run by and for the very people who participate in our oppression.