The Personal Histories of Intimate Objects

from Nina Simone's Gum and the estate of Joan Didion, to the faded receipts in charity shop books

Since November, I have not only experienced the quiet joy of working in a bookshop but also that of becoming the gentle handler of other’s lives. In the pages of discarded literature, I have become the accidental custodian of birthday cards, Giro cheques, train tickets, hand written letters, notes on the opera, adverts for dancings lessons, magazine cut outs, ancient Woolworth’s receipts, handwritten poetry, and endless devoted inscriptions - ‘with love’.

What is it about these scraps of the mundane, the banal, that I find so fascinating?

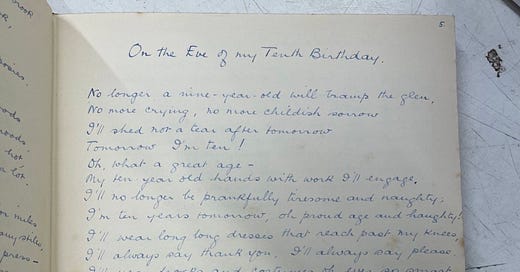

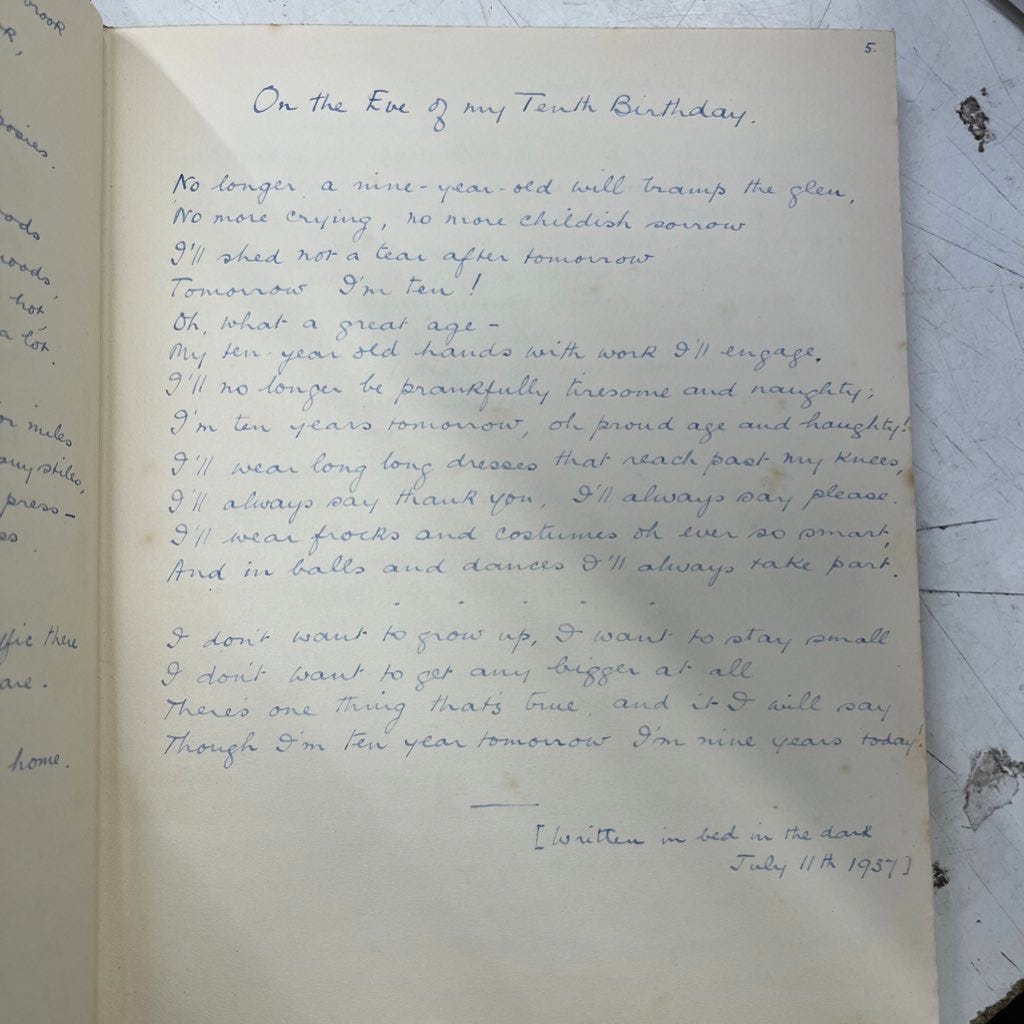

Perhaps it is because I am a sentimentalist. By that, I mean that I have a tenderness for people and places and objects and all the ways in which these things inescapably interlink across stretches of memory, in the act of simply being and existing. It is, then, the intimate serendipity of chancing upon these personal paper trails that captivates me. My hands take hold of casual artefacts, those left behind traces of what we have done and who we were. I am given access to snapshots of a life, tiny moments which I can never and will never be able to delve further into. It is an understanding that occurs through fragments. Someone’s meticulous notes on Russian ballet are a love letter that I feel adoration pouring from. The clarity of mind of a nine year old on the brink of her tenth birthday bowls me over, with so many decades of time between her feelings then and my eyes over her words now.

This is the kind of history that I am warm towards. Objects like these have a transportive quality. Their physicality and concreteness manufactures a link between present and past, a conversation stretching across time that allows the then to still exist in the here and now. It is simultaneously transcendent and utterly everyday. Here are the echoes of thoughts, actions, touch.

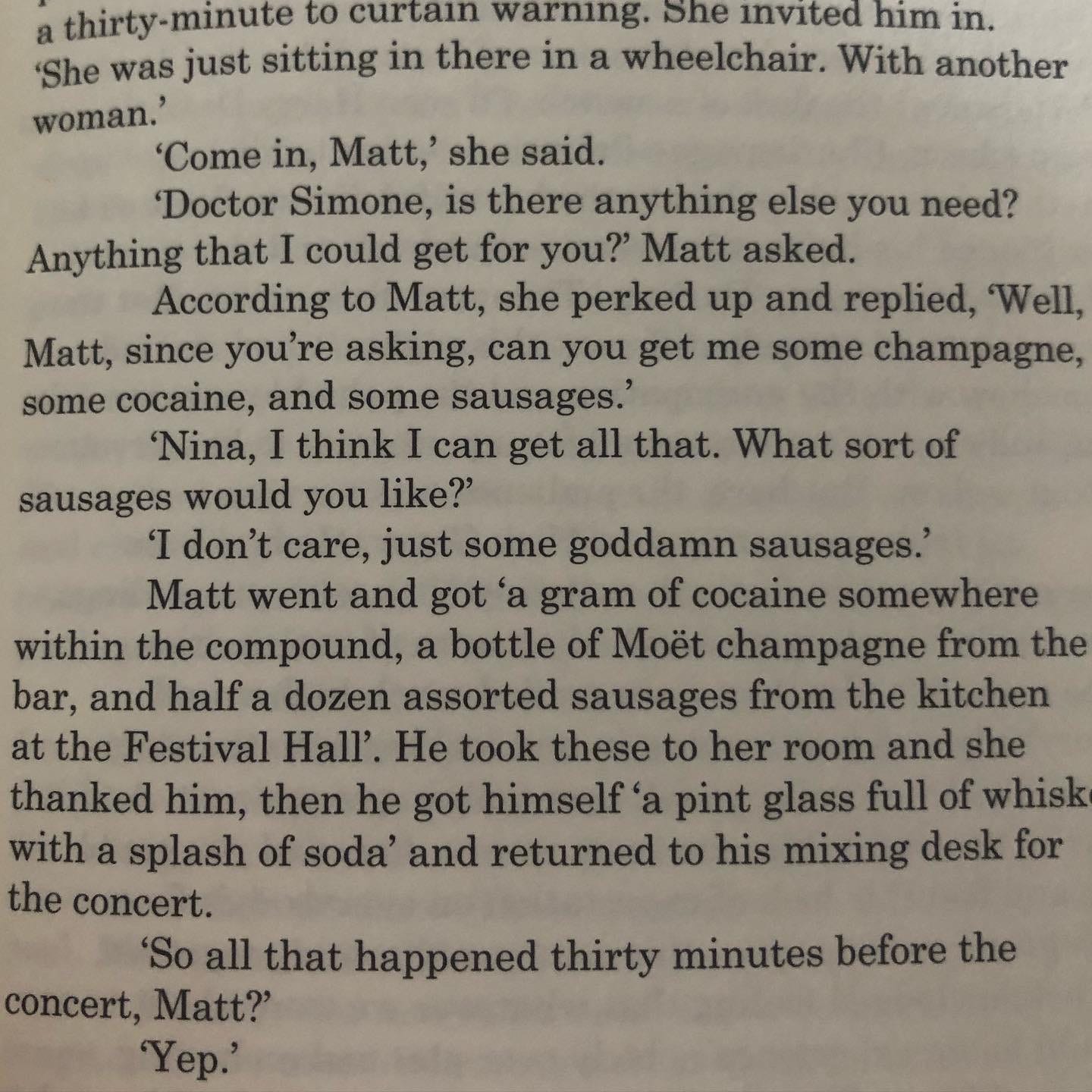

Earlier this year, I read Warren Ellis’s wonderful book ‘Nina Simone’s Gum’, an ode to sentimental object hoarding. It follow’s Ellis’s journey with a piece of Nina Simone’s gum, which he had crawled up onto the stage to take from her piano post-performance. The gum was kept safe and secret, wrapped up in a towel and plastic shopping bag until Nick Cave suggested to Ellis that he might exhibit the piece.

The gum becomes something of a relic - or perhaps it always was, with Ellis just the first to see its sacred value. It’s aura is felt by all who encounter it, it’s preciousness never challenged but understood with a shared feeling of it’s inexpressible significance. One can see a piece of chewing gum as transient - something discardable and temporary in any other scenario. And yet, Nina Simone’s teeth are the ones who touched it. Moulded it. In it’s shape is forever cast the pattern of her teeth. It transports us to her performance, carries something of her that cannot be explained in mere words.

Kat Lister recently wrote for Vogue on Joan Didion’s estate auction, similarly highlighting why we value other’s personal objects. In this article, Lister gives a name to this phenomenon (for which I am utterly indebted to her) - ‘what 19th-century anthropologist James George Frazer called "sympathetic magic"'.

‘Sympathetic magic’ is that very act of transcendental connection between object and person, an act that makes a piece of gum, a Le Crueset, a scrap of writing more than that. It is a portal, a key to another existence, a looking glass through time and space.

Didion fans’ desire for her various items are a desire to connect with her, an attempt at getting closer to someone they never can. But Lister reminds us that this kind of ‘sympathetic magic’ can be closer to home. In finding an army badge belonging to her grandmother’s tragically killed lover - a man Lister never knew - she is intrinsically linked to a life she otherwise could have never connected to. It is the presence of the item, it’s somehow aliveness that allows her to feel such a bond.

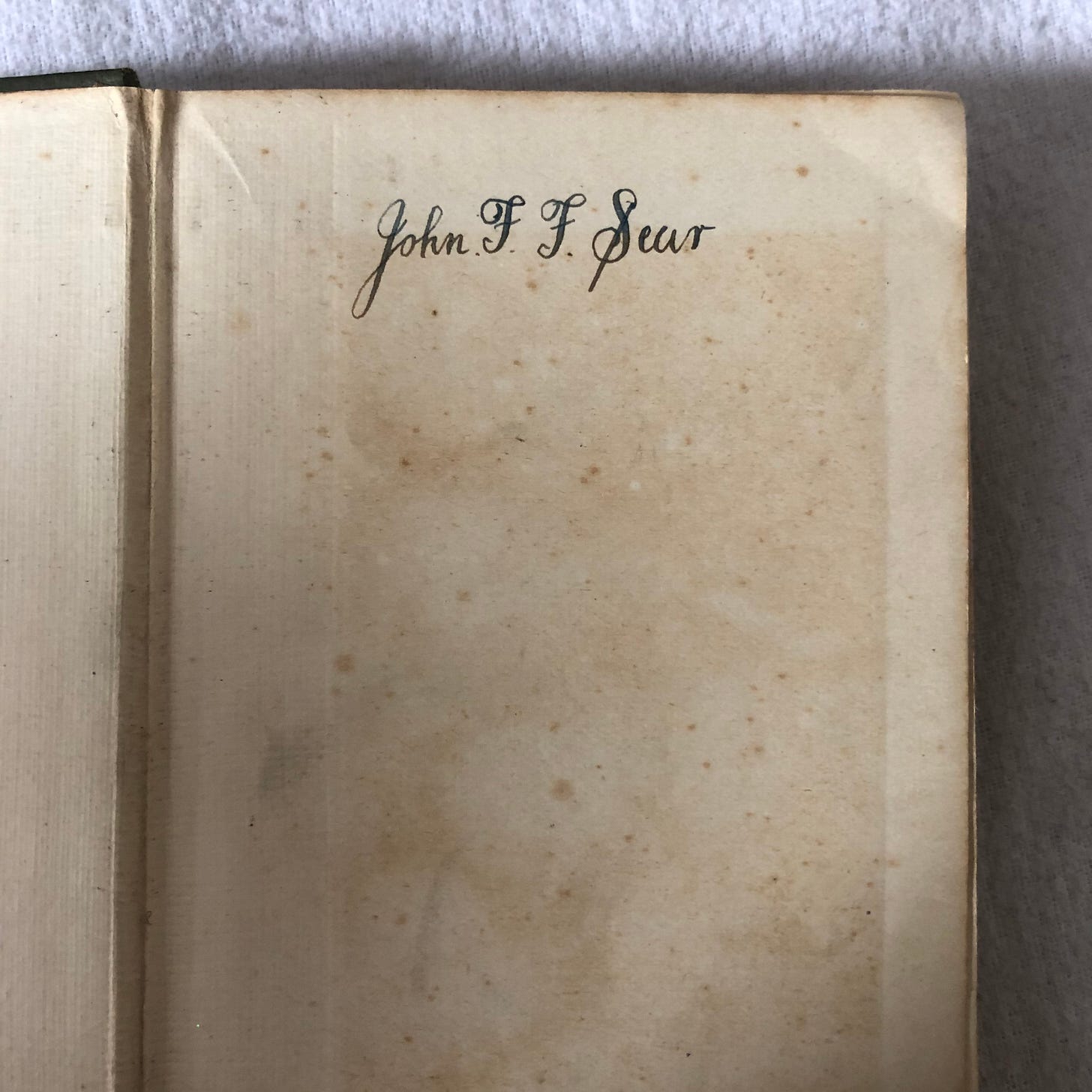

In April this year, I found a beautiful, green, cloth-bound book of Percy Shelley’s poems on our living room shelves that I’d never seen there before. The embossed gold lettering on the spine was gorgeous enough. But on the inner cover, the page yellowing with age, was a signature in enviable penmanship - that of my great grandfather ‘John F.F. Sear’. As I flipped through the pages, I found poems underlined with a delicate and wonky hand. In other places, there were tiny notes marked in the margins; signs of former studying, thoughts being captured permanently.

I gained his Milton and Wordsworth books from my Nan. With these books, it was as if the text as an interface took on a whole new meaning. Within those underlinings was a means to decipher a past. Were these pencil marks merely educational, for examinations and academia? Or was there an emotional attachment to those words? To that passage in Paradise Lost asking “for who would lose/though full of pain, this intellectual being /those thoughts that wonder through eternity”.

Of course, I will never know. I have no means to ever ask. But in this act of reading someone else’s annotations, there is an intimate means of accessing a seemingly unreachable personhood. And it is the same with it all - whether they are the objects of icons, the postcards of strangers, the scribbling of a family members a lifetime before me. These are the kind of histories that matter to me. The personal and the everyday.

When I hold these things in my hand, in the cold back room of the store, I feel something is reaching out and touching me so far beyond myself. It is in these little objects, the tattered scraps and abandoned items, that I am reminded of the infinite interconnectedness of being.

My goodness. What a beautiful piece of writing. And so poignant to me after just cleaning out my parents' house where I grew up and where they lived for 54 years. It wasn't the monetarily valuable things I wanted. It was the mundane, the every day. A cup from the cupboard, a table cloth. But oh! What memories the mundane represent.

A thought provoking article, thankyou.

I work in a library and it's amazing the number of items we find left in books, but we are able to trace the last borrower and return the items. Most of it is treasure but occasionally it is something gross, like a used ear bud or clump of hair. I have photos. But I digress from your article, sorry.

I sometimes wonder if I disposed of the keepsakes (clutter) from relatives and souvenirs of places, would their memory still live with me afterwards. Having them is a constant reminder.